Introduction

The 21st century has started with the emergence of a powerful new resource, aiding in the creation of obscene amounts of wealth over

just a couple of decades. “Big data” ... “Data is the new oil” ... In 2005, unique internet users hit 1 billion people. Around this

time Skype, YouTube, Facebook and Twitter launched; the shift to web 2.0 had truly begun.

These businesses have become completely embedded into daily life and in less than 20 years, have grown to acquire the largest market

capitalizations in the world.

The amount of information that is now being produced, stored and consumed is so vast that it is quite impossible to conceptualize. As

more of our personal data is harvested by different businesses with varying interests, the risk grows for the potential theft, misuse and

exploitation of this digital treasure trove. This risk comes not only from malicious individuals, but also organized crime, bad political

actors and unscrupulous business owners.

In 2018, the company ‘Cambridge Analytica’ became infamous following whistleblower reports alleging severe misuse of Facebook

data that was collected without users’ consent. In 2017, Equifax suffered a large scale data breach exposing the

private records of roughly 150 million citizens across the world. As of 2020, the value of the data economy

between the EU and UK exceeded 400 billion euros and is projected to more than double by 2025. Securing the rights

and ownership of this data and finding the best solution to keeping it safe, will be a growing challenge.

Blockchain technology may offer a novel alternative to traditional data storage techniques, with disruptive potential to industries such

as finance, cloud computing, social media and data security. Although the meteoric growth of Bitcoin popularized the concept of

distributed ledgers, there are a number of other interesting blockchain platforms rapidly evolving and attracting a range of talented

software developers, engineers, cryptographers and IT professionals.

History

The term blockchain was coined from Satoshi Nakamoto’s 2008 white paper named ‘Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System’. The paper describes a protocol for using a network of anonymous computers (chain) to process batches of digital transactions (blocks). While it was Bitcoin that propelled the term ‘blockchain’ into the global lexicon, various iterations of technologies similar to blockchain had been conceptualised and implemented many years prior to its arrival.

David Chaum, an American computer scientist and cryptographer, can be considered as one of the first to have documented a method for computer based distributed public record keeping. The vault system, described in his 1982 dissertation ‘Computer Systems Established, Maintained, and Trusted by Mutually Suspicious Groups’, incorporated many of the design elements used in current blockchains. Chaum’s system did not however provide a mechanism for achieving consensus with unreliable communications and typically required ‘level 2 trustees’ to verify and authenticate nodes. Over the following years Chaum continued to work on a variety of applications centred around cryptography (introduced blind signatures), distributed systems (communication mixers) and digital payment methods (DigiCash).

In 1991, Stuart Haber and Scott Stornetta published their ideas on how to certify the chain of ownership for digital content. They discussed the growing importance of ensuring digital documents have not been tampered with and provided a theory for timestamping data in a way that would make it impossible to change the original document without it being apparent. A year later they incorporated Merkle Trees into the design, together with timestamping and a hashing algorithm it essentially started one of the oldest known blockchains. Haber and Stornetta developed a product named ‘AbsoluteProof’, this software enabled clients to cryptographically seal their documents; although it does still rely on a centralised server to timestamp each entry, it features many aspects of a blockchain.

A number of different people over the next decade contributed in some way or another to the realisation of blockchain. Cynthia Dwork and Moni Naor proposed Proof of Work, an essential component of Bitcoins consensus mechanism. It was used in the popular system ‘Hashcash’, an application that limited email spam and DoS attacks. Nick Szabo designed a decentralised digital currency called ‘BitGold’, it was not implemented but has been labelled as a direct precursor to the Bitcoin architecture. Around the same time Wei Dai published a paper on ‘b-money’, this document outlined all the properties of current cryptocurrency systems and described the core concepts that were later implemented in Bitcoin.

When Bitcoin launched in 2009, it aimed its sights squarely at the financial system with a message coded into the first block, ‘The Times 03/Jan/2009 Chancellor on brink of second bailout for banks’ . Its purpose was purely transactional, a way to anonymously make payments across the internet without any requirement for a centralised or trusted authority to mediate the exchange. This achievement was built on decades of academic literature, combining various cryptographic standards and cypherpunk ideology into a single application. For the first time, a truly decentralised and secure method to transfer data was out in the wild. This triggered an avalanche of progress as people used, forked and iterated upon the newly developed standard.

There are currently over 1,000 blockchains and 18,000 cryptocurrencies. Blockchains such as Ethereum have paved the way to decentralised applications that can run with no server downtime and nonfungible tokens for various digital commodities. Projects are being developed and implemented across various industries including supply chains, banking and finance, entertainment services, retail, healthcare, real estate and charity platforms.

With large corporations now actively investing in blockchain solutions and government bodies slowly accepting and regulating this technology, it certainly appears that distributed ledgers are quickly moving past the ‘hype’ phase and into a more legitimate and practical era.

How Blockchains Function

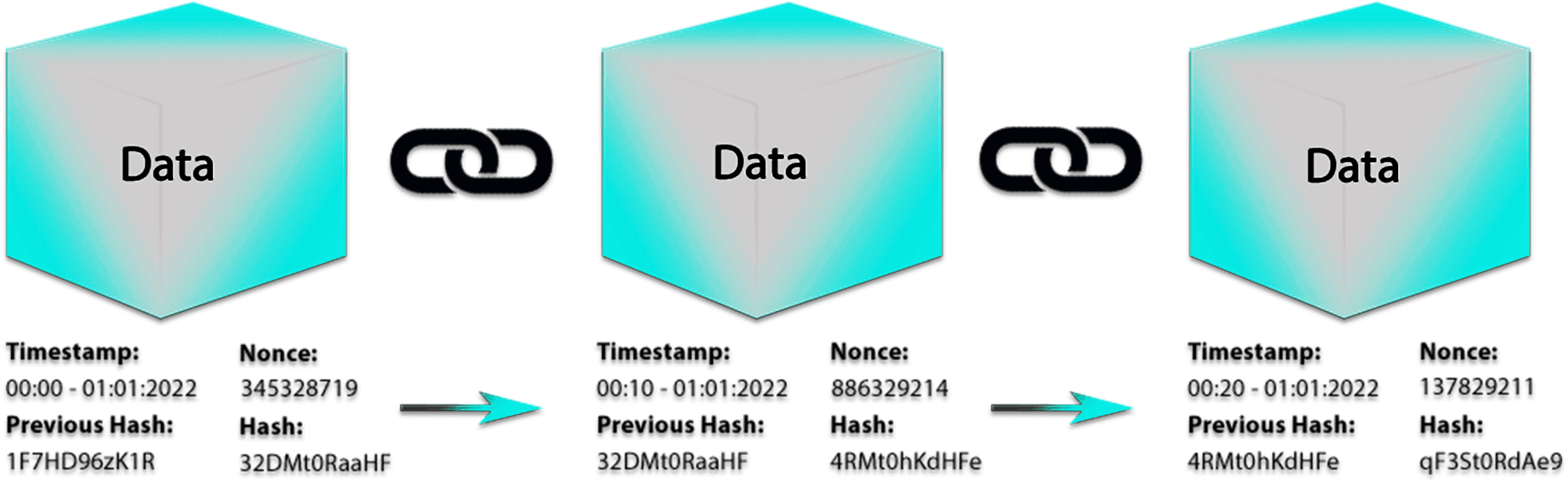

A Blockchain can be considered as a type of database. At its core, it is a digital ledger that typically stores information about transactions. The data is stored in chunks named ‘blocks’, these blocks are signed and linked to each other creating a ‘chain’ of irreversible data entries. It is important to note that data can only be appended to a blockchain, it cannot be modified, inserted or deleted at a later stage.

There are two main types of blockchain, public and private. The essential difference between them is that in a public blockchain any node can join and leave the system, whereas in a private chain there is always some form of access control or membership system for participating nodes. In a private system nodes can focus purely on processing data entries, due to being pre-vetted they can be trusted to read and write without any disruption. They are often high throughput but sacrifice some level of decentralisation depending on the methodology, this approach can work well in an enterprise setting where server access can be tightly controlled. In contrast, public blockchains have a challenge to solve as nodes in the system may wish to attack the network or process false entries, how can agreement be achieved regarding the correct state of the database in an environment that is potentially hostile?

Power! Give me all the power!

Blockchains that enable services like Bitcoin are dependent on substantial amounts of energy and have frequently been in the news for the large electricity demands needed to ‘mine’ coins, but what does mining Bitcoin actually mean?

Put simply, mining is the process in which computers complete some work and are rewarded for the effort with newly minted coins. Like mining for gold, energy is expended and as a result something of ‘value’ is attained.

This leads us to the next set of major differences between various types of blockchains, the ‘consensus mechanism’. To solve the problem of trust in a decentralised network, various approaches have been taken. Proof of Work (PoW), Proof of Stake (PoS), Delegated Proof of Stake (DPoS), Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance (PBFT) and Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) are currently the most commonly used algorithms.

The above graphic shows a simplified representation of the PoW consensus mechanism used in Bitcoin. When a user wishes to submit data to the blockchain they announce it to the network, nodes then collect pending entries and group them into a block. Appending a block to the chain is not free, PoW requires that the ‘miner’ (node) uses up resources for the privilege. All of the data in the block, along with a timestamp and reference to the previous block, is passed through a hashing function; which acts like a fingerprint unique to each block. Added to this is a variable called a nonce, this is a number that changes with every hashing attempt. The goal of the miner is to repeatedly guess hashes (altering the nonce each time) until one is produced that meets the required difficulty standards dictated by the protocol, this difficulty changes as more or less nodes contribute their resources to the network. The higher the hash rate, the more difficult it is to find a valid hash. Once the requirement has been satisfied, the miner broadcasts the result to the network and participants validate then update their chain to include the new block. The winning miner is rewarded for their efforts with newly minted Bitcoin, this process makes it expensive to try and cheat but profitable to act honestly. Together with public key cryptography to secure each ‘wallet’ (account), the mechanism provides a secure way to transact anonymously with no requirement for a centralised server.

Okay, so people can have a decentralized database... is blockchain able to do anything else?

Yes!

In 2014 Vitalik Buterin published the Ethereum whitepaper. Using the PoW consensus mechanism, Buterin expanded on the idea of a

decentralised database to also include what is now known as ‘smart contracts’. The intent of Ethereum was to create a protocol for

operating decentralised applications (dApps), it features a Turing-complete programming language called ‘Solidity’ and lets

programmers write scripts that can be stored and executed by the blockchain itself. This had a large impact on the

blockchain community as users could now create their own ‘tokens’ with a few lines of code and leverage the existing Ethereum

ecosystem. Different ideas for dApps are still being developed every day, any software that needs a secure and immutable database

can make use of blockchain technology and the resources of a vast global network of computers.

In a future update, Ethereum developers intend on making a major change to its consensus mechanism in an effort to curb energy

consumption and improve scalability of the platform. It will move to PoS, which replaces ‘miners’ with ‘validators’. Instead of guessing

many hashes these validators will lock (stake) value into contracts, if they ‘misbehave’ their funds will be slashed and they will

potentially face exclusion from the network. Blocks are randomly assigned to validators and rewards will be in the form of transaction

fees instead of newly minted coins.

So how many people actually understand blockchain technology? When asked, survey results show that only 22% of individuals have

an idea of how it functions with 72 out of 92 respondents answering no and only 20 answering yes. A similar ratio can be seen

regarding NFT (non-fungible tokens), 28% of those questioned had an understanding of how it works. With the recent ‘hype’ over NFT,

it is possible that more people have begun taking an interest in this particular aspect of blockchain.

Criticisms

Certainly nothing is perfect, the benefits that blockchain technology brings comes with downsides. One already mentioned, energy

consumption, is becoming more of a problem as time passes. Estimates on the exact environmental cost vary, it is difficult to fully

calculate given the distributed nature of participants and varying properties of their hardware. A reasonable scale for the electricity

consumption of Bitcoin per year is between 60 and 125TWh, which is more than entire nations. A single block is said to require similar

electricity needs as a German household would use in weeks, even months. Given blockchains such as Ethereum

have applications that rely on processing many small transactions (over 6000 blocks and 1 million transactions confirmed every day),

this problem is a priority for future development to resolve.

In regard to the environmental costs of maintaining a decentralised blockchain, one lesser spoken concern is the vast amount of

electronic waste attributable to mining. Large server farms containing thousands of custom built computers run 24/7, once they reach

low efficiency rates they are typically discarded (Bitcoin is optimised for ASIC mining). Ethereum ‘mining rigs’ consist of consumer grade

GPUs, putting pressure on supply chains and recycling facilities.

Scalability is another big issue with current platforms. When the networks see a spike in usage, fees often become untenable for

microtransactions. In the case of Bitcoin, the current native maximum throughput is about 7 transactions per second while Visa can

achieve more than 4000 transactions per second. It can take 30 minutes for a transaction to be considered fully

confirmed on Bitcoins blockchain, which is not practical for a frequently used ‘cash-like’ currency. There are numerous solutions to

improving this issue, the Bitcoin lightning network is becoming more popular and Ethereum aims to change its consensus mechanism.

Other blockchains that run algorithms such as Proof of Stake and Directed Acyclic Graphs offer much higher throughput at a fraction of

the energy cost, various projects exist to bridge different blockchains to eventually result in a ‘cross platform’ ecosystem.

Once entries have been confirmed on a blockchain, they cannot be altered. This in itself, although for some applications a benefit, can

also be a hindrance. For example, what if a mistake is submitted to the chain? What if a flaw is discovered and a user is able to siphon

funds or data and there is no mechanism to reverse this error? This exact scenario has occurred before, a bug in a platform launched

on Ethereum resulted in a large scale exploitation and theft of millions of tokens. What happened next was extremely controversial in

the blockchain community, the Ethereum developers decided to ‘roll back’ the chain and fork the project after patching the bug. This affects trust in the system, which as revealed by the survey is already quite low. With only 25 out of 92 respondents stating

that they trust blockchain technology, there is a long way to go before users will be willing to incorporate blockchain into their daily

lives.